In Community with the Past & Present: Black Women Educators, Ancestors, & Descendants

March uprooted me.

My brain was doing what I thought I’d been training it not to do: contemplate everything at once. Was I going to accept Harvard’s graduate school offer? Where was the money going to come from? Should I create Women’s History Month content for socials? I have to stay relevant for my forthcoming book. By the way, when are those edits arriving? What poems would I use as exemplars for my middle-school class? Should I write one? Which client’s work was a priority once I returned home?

I pulled my arm from under the pale blue sheets and did my best to avoid the wires tied to the gadget monitoring my heartbeat. I stuffed my arm into my workbag on the chair beside my Northshore Hospital bed and pulled out my phone. Whenever thoughts like this consumed me, I needed to list them, preferably with a soundtrack. Aiming for Samara Joy or Jazzmeia Horn, my finger slipped into my streaming app to audiobooks, and Imani Perry’s Audible exclusive “A Dangerously High Threshold for Pain” popped up first. The image on the cover was like looking into a mirror. It was a Black woman in a blue hospital gown with the title in capitalized font slashed across her chest, and I imagined mine would say, “How did we get here again?”

I could not see the forest for the trees, so God had to see it for me.

I found Imani’s work on a book table at Medger Evers Black Writer’s Conference at 19, and I’ve been influenced by her words ever since. God knew this and was using Imani to speak to me.

I immediately pressed play, and Imani’s soft but firm voice poured into my ears, “To know oneself as a person who lives with chronic diseases, however, is not the same as having reflected upon that living. It is a flood. There are traumatic events. They range from relatively minor things, such as a phlebotomist who must prick you fifteen times to get your blood..”

I had to pause the audio for an incoming nurse to do precisely this task. Ouch. He informed me that I would be seeing many doctors stop by that day: one for my intracranial hypertension, another concerned about my A1C level, and the last to review the scans they’d done to ensure the pain in my chest wasn’t emitting from my heart.

The alignment between Imani’s words and the nurse was a white flag swinging above my hospital bed. I knew God was asking me to surrender. She told me it was not the time to analyze, process, and plan my work tasks but to speak life into myself.

This was only her first warning, her first yell, and the next would arrive shrouded in history.

In February, I was invited to take a “sojourn” in March courtesy of the Harriet Jacobs Project, helmed by Johnica Rivers and Michelle Lanier. Harriet Jacobs was a Black freedom seeker, educator, and writer whose autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, was published in 1861. I read this work at Hampton University during my undergrad years.

In her email, Johnica Rivers described the Sojourn for Harriet Jacobs as “an invitation to put skin to the soil that held Jacobs's feet and to look upon the waters that carried her to freedom.” The breakdown of the proposed experience was a dream: a stay at a spa hotel, a Jacobs and Carolina-themed dinner with an “interdisciplinary group of Black women artists, scholars, writers, and cultural workers” from across the globe, and a trek to retrace Harriet’s steps in her homeplace of Edenton.

The sojourn was the same weekend I needed to attend Harvard Admitted Students Weekend to make my final decision. I traced my fingers on my laptop screen to figure out if the dates would work, and they fit like a puzzle: poetry class with my students on Tuesday, arrival to North Carolina on Wednesday, and depart for Harvard on Friday.

I devoured Imani’s book in the three days I spent in the hospital bed, and each chapter’s title plucked me like a guitar: care, caretaker, collapse.

Erica, take care of yourself; let people and events care for you before you collapse.

The doctors could not figure out the cause of my chest pain, but by the end of the visit, it was gone. The last doctor who came to see me, an older white man who looked at his watch more than me, said, “Perhaps you just need to lose some weight.” How American.

My father came to pick me up from the hospital and told me that instead of leaving, we needed to go to the 6th floor. He did not have to give me more details because I already knew my mother was there, too.

“Her back?” I asked.

He nodded.

My mother sustained three herniated spinal discs in an accident in the '90s, an injury that never fully healed. Despite physical therapy, frequent doctor visits, and the soothing relief of tiger balm, the pain returned every week like clockwork. Yet, no matter the discomfort, she showed up daily to a job where she cared for the city’s children.

My mother and I have always been echoes of one another. When NY & Company was still Lerner Shops, she took me there every month to "grab a few good shirts for work." She is my hero, my first teacher. I wanted leather boots and bootcut work pants instead of platform Spice Girl Skechers and bell bottoms. I longed to be sharp, crisp, and never wrinkled. But my mother never warned me that we, too, would crease—that we’d be folded into microaggressions, our worth sharply underappreciated. With all her heart, she believed her work and faith would carve a better world for me. And while that vision holds true within the safety of our home, the world outside would rather see us hospitalized than promoted.

I spent the night she needed to stay in the hospital in an oversized chair by her side. I stayed awake looking out the window at the twinkle of Northshore Hospital and the grounds across the street, seeing the world in layers as I always do—a bridge between the past and the present. Across the street was a Black and Shinnecock burial ground and the preserved Lakeville AME Church site.

On the way to the hospital, I thought about the Black and Indigenous town that once sat there and how suburban Long Island’s development, including the hospital’s need to sprawl out over more land, had continued to swallow its memory whole. I stopped there on my way home.

Someone had taken the new preservation sign that noted the church’s burial site as one for African Americans and Native Americans and crammed it into the center of a tree. I imagined the tree’s pain, considered its center as its spine, and thought of my mother.

My mother had always been my guiding star, but perhaps I needed to be hers—word to the Harriets. She was nearing retirement, and I wanted her to see that she deserved every bit of life left.

I looked down at the grounds with scattered yellow fig buttercups, said a prayer for the ancestors, and made my way home, determined to do whatever I needed to rest and reset: sleep, get up, pack my bags for North Carolina and Cambridge, and leave everything else in New York.

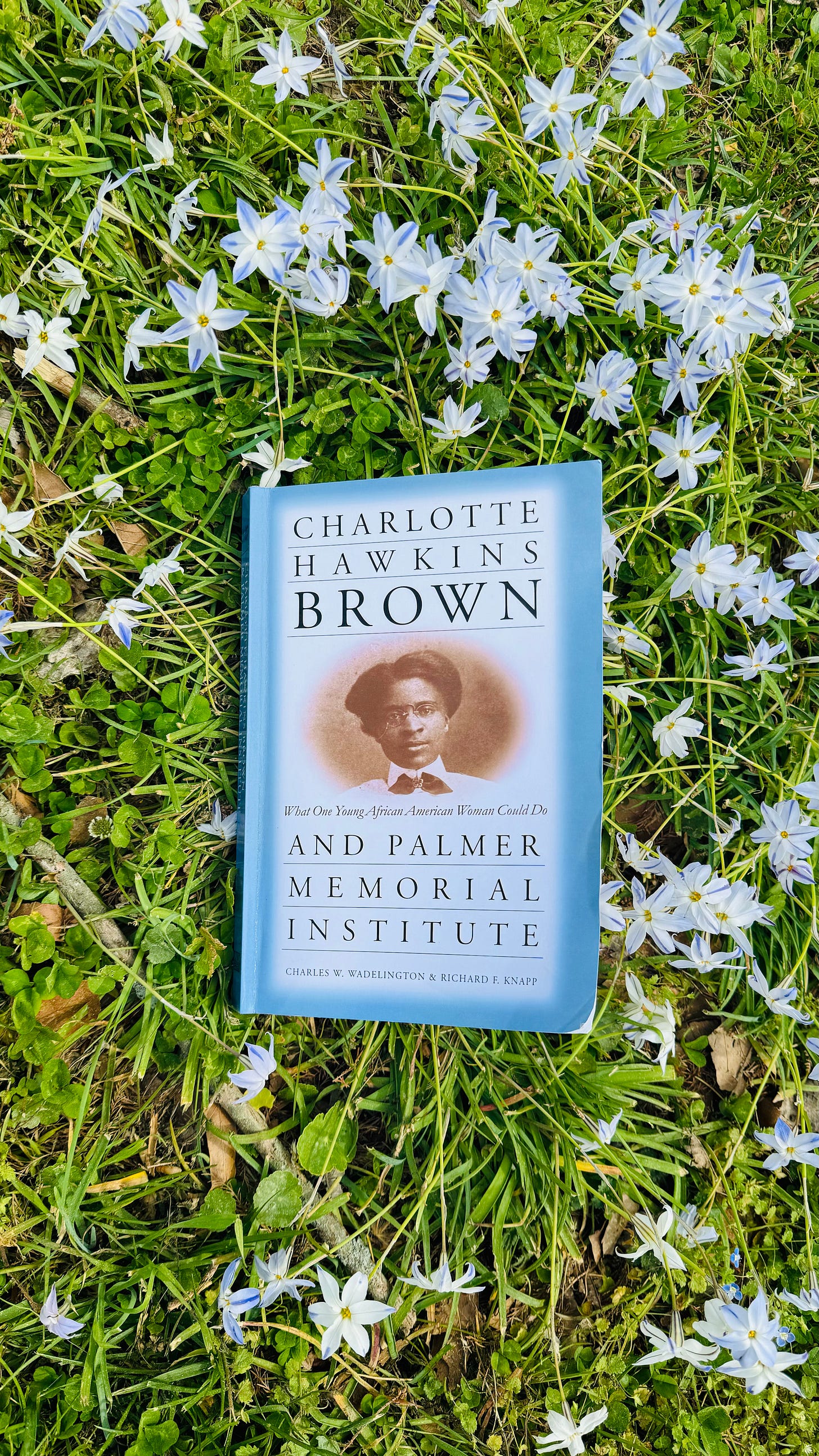

I decided to take my favorite form of travel to North Carolina: the train. On the train ride, I crack open my thick journal for the first time in a while and stick receipts, stickers, memories, and words in it. I aim to make the pages as colorful and seemingly tactile as Lois Mailou Jones. I’d been posting Jones’ work on my Instagram stories, and Johnica replied to let me know that Jones was the first art teacher at Palmer Memorial Institute, now Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum in Sedalia, North Carolina. I realize it is only an hour from where I’ll be staying. She offers to coordinate an extra leg of the trip just for me. I graciously accept.

As the world moves outside my train window, I count all the Black women I am grateful for. Amtrak’s route down the East Coast is fascinating, as is watching the landscape shift from trainyards and skyscrapers to small church steeples and farmland. A friend waiting for me at my final destination applauds my efforts to slow things down:

Jessica Moore Matthews, an expert in equipping Black women with everything needed for a successful campaign, is the person you want waiting for you at the station. She and her husband are close kinfolk. They were my play siblings at Hampton University. She pulled in with her daughter, named for George Washington Carver, and our smiles widened as the car drove in. We drive through Raleigh, and she brings my attention to the new Black children’s bookstore downtown, forced to move a month after my visit due to numerous threats, a plethora of trinket stops that the antiquarian in me beams about, and SNCC’s founding place at Shaw University and all things Ella Baker.

Jessica and Carver safely get me to the hotel after a lovely meal, and I spend the next three days doing what I set out to do: reset.

I can hear God every step of the way.

I can hear God as I make my way to Sedalia on the first day of the retreat. After reading James Anderson’s The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, I became fascinated with the educators of the diaspora with whom we are in lineage. While I was the product of a Historically Black University, I was still coming to terms with the nuances of Black schooling. Many of the institutes established by Black 19th-century founders were created through scraping, saving, community, church, prayer, and sheer will. When the cab pulled up to the former Palmer Memorial Institute grounds, I began to cry. It’s one thing to read about the work, another to “put skin to the soil” as Johnica would say.

I can hear God as I discover that the school’s founder, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, made her way to Sedalia from Cambridge, Massachusetts, spent time at Harvard, and one of her funders was Harvard’s longest-term President, Charles W. Eliot.

I can hear God as I learn that Brown brought Jones to start her art department and Langston Hughes to establish her English classes. She was a curator of educators, getting them to places where they could serve Black children. I saw myself in her legacy.

I can hear God during a conversation at a dinner table with a journalist who writes only about the feats of Black women, a non-profit owner purchasing and preserving the homes of Civil Rights activists, and a student who has just opened her first art gallery for those who paint in brown skin. In the middle of dinner, Johnica gives a speech, and she says, “It is not enough to read the book; it is not enough to go into the archive; you need to go to the place.”

Go to the place.

Go to the place.

Go to the place.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Syllabi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.